This article was originally published in The Notebook. In August 2020, The Notebook became Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

Updated at 4 p.m. Dec. 21, 2017 with comments from the Mayor’s Office of Education.

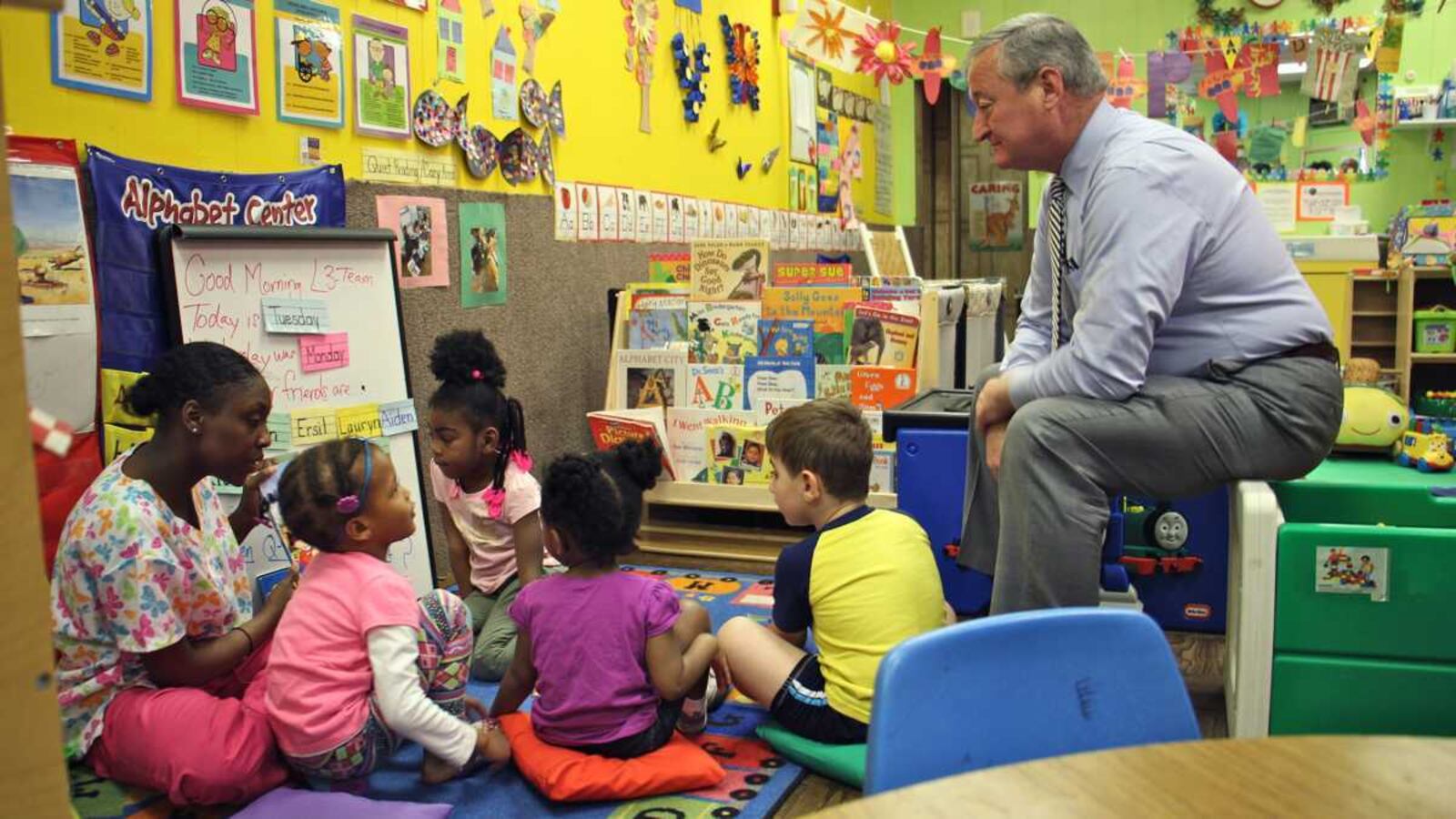

The city controller’s audit of the mayor’s new preschool programs – released Wednesday – found the program to be generally successful, although it has not fully expanded and lacks enforcement of the state’s quality standards.

The universal pre-K effort provides free preschool to students, 81 percent of which come from low-income families according to the Mayor’s office. It’s funded by part of the soda tax, which has raised less revenue than anticipated. Previously, the city has suggested that the shortfall may be due to retailers stocking up before the tax went into effect.

"Actually, revenue collections are doing quite well – about 15 percent short of original estimates," said Mike Dunn, a spokesman for the city, in an email. "Economists have reported that’s well within the normal range for a brand new tax. Additionally, $66 million dollars in the first 10 months of collections still represents a significant sum in a city where more than a quarter of residents live below the poverty line. And, most importantly, it’s still going to allow us to support three programs – pre-K, Community Schools and Rebuild for parks, rec centers and libraries – that we wouldn’t have otherwise been able to fund."

The audit found that the program has only enrolled about 2,000 children out of the 6,500 pre-K seats it initially sought to create. It was scaled back until a pending lawsuit against the soda tax, brought by the beverage industry, is resolved.

The audit applauded the programs for their administration and performance, providing bilingual teachers who speak Spanish, and accommodating children with physical handicaps and students of minority religions.

But the audit also found “missteps” due to a rushed process of implementation. The program was overbilled for $102,350 for children who enrolled but never attended their child-care sites.

Sarah Peterson, spokewoman for the Mayor’s office, said their office has not been shown those records.

"Our hubs work closely with providers to verify enrollment during the invoicing process," Peterson said in an email. "Also, PHLpreK’s reimbursement process compares favorably to other publicly funded ECE programs because we pay invoices based on actual enrollment after the fact, whereas Pre-K Counts and Head Start pay providers up-front."

Part of the program involves ranking providers by their quality and giving providers that are found to be below quality standards some time to improve. The city uses the Keystone STARS system to evaluate quality. The system, implemented by the state Department of Education in 2002, assigns a ranking of one to four stars based on staff education, learning environment, leadership/management, and family/community partnerships.

At the start of the program, 39 agencies, or 44 percent, joined at or below STARS level 2. To date, more than half of those providers have improved their quality, leaving the city with 18 agencies, or 20 percent, that still have not met quality standards for STARS level 3 or 4.

Otis Hackney, the city’s chief education officer, responded in a letter to the city controller, Alan Butkovitz: “The report suggests that partnering with lower-quality pre-K centers was due to a ‘rush’ to implement PHLpreK. This is simply not the case. The City was always transparent about its quality improvement strategy. This strategic investment has already resulted in the elimination of five pre-K deserts.”

Hackney argued that the lower-quality pre-K programs were only chosen when necessary to offer programming in neighborhoods that would not otherwise have it and that most of those providers had since improved their quality.

Butkovitz recommended that the city establish formal written policies for removing pre-K providers that fail to meet those quality standards within 18 months.

Hackney said in his letter: “At the end of the 2017-18 school year, we intend to assess providers’ continued participation in PHLpreK on a case-by-case basis and will only continue to partner with those that have a demonstrated commitment to improving the quality of their program. We will remove providers from PHLpreK that have not shown growth in key areas.”

The audit found that many providers are not paying their business and wage taxes and recommended that the city monitor providers for compliance.

"We already monitor providers for tax compliance on a monthly basis with help from the City’s Revenue Department," Peterson said. "Whenever we find a provider has fallen behind on their taxes, Revenue works with them to either settle the balance in full or enter into a payment agreement that will help them catch up."

Butkovitz also took issue with the way the city was accounting for revenue from the soda tax. That revenue is deposited in the city’s general fund, and not a special revenue fund used to ensure that money is spent on a specific project or for a specific purpose.

“There is no guarantee that these revenues will be used for the supposedly ‘dedicated’ purposes,” Butkovitz said in a statement. He recommended that the city place the soda-tax revenue in dedicated funds.

"The Philadelphia Beverage Tax supports projects beyond PHLpreK, namely Community Schools and Rebuild," Peterson said. "The City’s Finance Department, following best practices in government accounting, views a special revenue fund inappropriate for this broad use of revenue, as the funding is not limited to one specific project."

The full audit can be read or downloaded here.