It was a typical winter Saturday, and my family and I were walking home from dinner at our favorite Mexican restaurant. I was wearing an oversized gray knit sweater, a hand-me-down from my grandpa.

I was 13 and obsessed with oversized clothing that hid any curves. I always wore my hair in a ponytail and felt envious around boys my age. Sometimes when I looked at myself in the mirror and in photos, I felt that someone else was looking back at me. I felt strangely disconnected, as if someone had taken a knife and severed the connection between my mind and body. Now, in a lightning-fast moment of epiphany, I knew why.

As the sidewalk passed beneath my feet, a single sentence sprang from my subconscious and repeated over and over in my head like a chant: “I’m not a girl.” The words caught me off guard. A part of me immediately knew they were true, and that was the scariest thing in the world.

As an eighth grader with a strong desire to fit in, I found it difficult to fathom a world in which I was not who I was told to be. My parents had raised a daughter. My friends were friends with a girl. I was a granddaughter, niece, and sister. My assigned gender was so embedded in me that I wondered if I would survive if I reached in and ripped out those roots.

I was afraid of becoming an alien to everyone and everything I knew. At the time, I did not know a single trans person. I thought that not being a girl would mean becoming estranged from my friends and family, that being myself meant not belonging.

I got into bed still wearing the gray sweater, and, lying in the darkness of my bedroom, I stared up at the ceiling. I knew that this realization marked a definite, massive change in my life. I did not know if I was ready.

But the voice in my head kept sounding.

The only thing about my identity that I knew for sure was that I wasn’t a girl. But the possibility of being a guy was so strange to me, so against the norm, that I couldn’t even bring myself to consider it. So after I learned the term online, I figured that I must be non-binary.

Seeing other trans people online made me feel a lot better and less alone. I learned about gender therapy, trans clothing brands, and barber shops. This knowledge lessened the internal pressure I felt because I knew I could do something about what I was feeling.

At the same time, the more I knew about my identity and the more I considered my future, the more I hated what I looked like. As my gender dysphoria got worse, I would stand in the mirror with my shoulders slumped, hiding my chest. I would stare at my long hair and eyelashes with disgust.

The pressure of feeling stuck in my body grew until I was ready to burst. I had to tell someone. So two weeks after my epiphany, I decided to tell my family during dinner.

Tears poured out while I spoke to my family, telling them I was non-binary and wanted to go by the name Ash, which I found on an online list of gender-neutral names. My sister and mom cried, too, while my dad looked confused. Although initially supportive, they were worried and uncertain how being trans would impact the rest of my life. The moments afterward were a blur, and I remember feeling afraid of the massive change.

The next year was the hardest of my life. We were in lockdown due to COVID-19, and the only time I left the house was to play softball, a sport that my dad took immensely seriously. I was closeted until my dad told my coach without my permission. Then I cut my hair and started using my chosen name, and there was no hiding my gender nonconformity.

But my voice and body still didn’t match how I felt. As time went on, my unhappiness and dysphoria made me more introverted, and I grew apart from the girls on the team. I felt other. I felt different — outcast, even.

One day in July, I was sitting in the dugout, the sun bearing down on me. Chatter from the game drifted in the summer air, and sweat dripped down my back. I could hear my team talking and laughing, but when I looked toward them to join in the conversation, I realized that they had moved down the bench, away from me. They seemed so at ease with themselves.

My assigned gender was so embedded in me that I wondered if I would survive if I reached in and ripped out those roots.

I prayed that one day I would leave this weird gray area, where I was not a boy nor was I accepted as a girl. Without saying anything and without bothering to move closer, I swallowed my tears.

I felt hopeless, unattractive, and worthless.

There were some positives, though. My parents took an active and supportive role in my transition and, during one of our conversations, they helped me decide on a new name, not Ash, which I had chosen in a rush, but Kai. I preferred Kai because my parents helped me choose it; my new name felt like a do-over for all of us. Soon after, I excitedly and nervously came out to my class on an advisory Zoom call. Then my math teacher helped me change my name in the school’s system. It was surprisingly easy. My mom just filled out a Google form.

I continued to ponder my gender identity. Sometimes people gendered me as a boy in public, and it made me happy. After many months of introspection, I realized that I wanted to become more masculine. I wanted more than “not a girl.”

The more I researched online and was exposed to the trans community, the less the idea of being a man felt terrifying and impossible. And so, I decided to explore the possibility.

My assigned gender was so embedded in me that I wondered if I would survive if I reached in and ripped out those roots.

The August before my freshman year, I went to a two-week sleepaway camp and started using he/they pronouns. When my friends called me he and him, a giddy feeling filled my chest, and I decided that I wanted to use those pronouns exclusively.

One day at camp, my sister called me her brother for the first time. It felt like there were fireworks going off in my heart. I was a brother, a son, a nephew, a boy. I finally felt that I was finally on solid ground and able to visualize who I was with clarity for the first time.

I didn’t tell my parents until that December, a whole year after I had come out as non-binary. I think they already expected it. At this point, I was dressing in a very masculine way, and they noticed.

The conversation switched almost immediately to options for a medical transition, which was everything I wanted at the time: to no longer feel separated from my body. I told my parents about testosterone gel, injections, and surgeries. To my delight, they were receptive.

After months of medical appointments and conversations with my parents where they made sure that I carefully weighed the potential risks against the benefits, it was decided. I would start testosterone sometime in the summer. Much later than I had originally hoped, but the promise still made me happy.

That summer I went to the same sleepaway camp as before, but this time I slept in the boys’ bunk. My bunkmates were all supportive, and it was the first time I had been truly affirmed by other guys. I even started dating someone from the girls’ bunk.

Having a girl like me as a boy was brand new and felt amazing. There is so much hatred online and in the world that made me feel that no girl would ever want to date a trans man, but that was entirely untrue.

One evening, holding a flip phone and lying on my back in a wet field, I dialed my mom’s number, anticipating the news that I could start taking testosterone. The night air was cool, and there were stars in the dark sky above me.

My mom’s voice sounded like it was coming through a tin can. After a few minutes, she asked, “Do you want to hear the big news?”

My heart stopped just a little, and I was smiling widely in the dark.

“Yes,” I said emphatically.

“The insurance company contacted us. Your testosterone is approved, and it’s waiting for you at home.” I could hear the anticipation in my mom’s voice, that she knew how excited this made me.

“Wow, that’s amazing. Thank you.”

After waiting for so long, her words brought a sweet relief. I would soon become more of who I was. I would look on the outside how I felt so strongly on the inside.

I could almost hear my mom’s smile and felt infinitely grateful to have such an accepting person in my life.

“You’ll start taking it when you get home from camp.”

All I could think was that I wanted to start testosterone immediately. I wanted to have a deep voice and muscles and stubble at once. But the news filled me with hope. I would become everything that I hoped to be.

After years of being publicly misgendered, constantly thinking of how my voice sounded and if I was passing, I would have the physical attributes of a cis boy. I was becoming a man because being a man in my head meant physically fitting into male gender norms.

After I hung up the phone, I walked back to the bunk, a faint yellow light illuminating the porch. The wooden steps creaked under my feet and I pushed through the mosquito netting hanging over the door. I turned to the first guy I saw, my friend Ethan.

“Guess what,” I said, not bothering to hold in my smile.

“What?” He asked expectantly. A few other of my bunkmates gathered around the two of us, hungry for the news.

”My testosterone was approved.” I blurted out, my grin widening.

“Yoooo!” Ethan yelled in unison with at least five other people. He dapped me up, then began chanting.

”One of us, one of us, one of us, one of us, one of us!” he hollered, clapping his hands. Everyone joined in, a thunderstorm of pubescent voices, and I was at the center of it all. My smile could only be described as beaming at that point. The chant continued until it was interrupted by a sleep-deprived counselor who staggered into the room.

”What’s going on?” he asked, raising his eyebrows at the commotion. I didn’t have to answer him.

“Kai’s testosterone got approved,” Ethan said, and his words were followed by a collective cheer. Ethan began the chant again, and this time the counselor joined in.

Emotions swelled in my chest as the echoing chant thundered around me. I was happy, of course, and laughing at the preposterousness of the whole situation. But I was also confused. I had slept in the same bunk as these guys, so why only now did I count?

I wanted to tell them that I was already one of them, that the testosterone didn’t really change anything, that it didn’t make me more of a man, but I didn’t. Partly because I knew that the testosterone would change so much for me, and make so many things better. And partly because the moment was so good and I didn’t want to ruin it.

Here I was in a rickety cabin in rural Massachusetts, a trans teenager being cheered on by 12 cisgender guys. Although the moment was complicated, there was no better feeling than fully exposing myself to everyone, showing everyone who I really am, and having them cheer for me with such fervor. It was one of the best forms of validation. The anxieties I had when I first came out now seemed distant.

By being myself, I wasn’t ostracized but embraced.

A version of this piece first appeared in Youth Communication. It is republished here with permission.

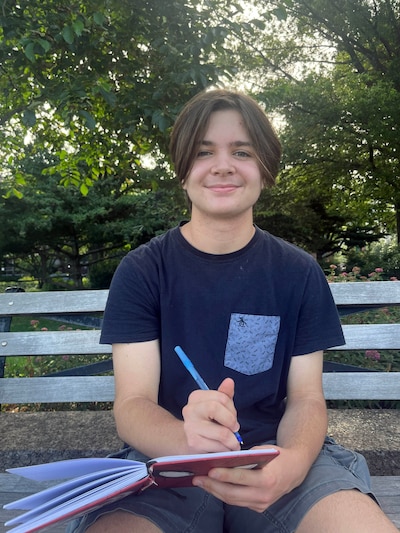

Kai Arrowood is a high school junior from New York City. His dream is to be a journalist and travel the world covering stories. In his free time, Kai likes to bake, write sci-fi, and listen to music. At school, he enjoys studying history and Spanish and writing for the school newspaper. He hopes to show the world that trans people are just like everyone else and are able to succeed despite the challenges they face.